Epic Sanctions Fail?

The U.S. Treasury Department just sanctioned an Iranian oil-smuggling network worth $300-million-a-year for Tehran’s coffers. But Iran’s Ministry of Oil said petroleum exports are at record levels.

Does this mean sanctions don’t work? Nah - policymakers are missing one thing.

First, why does it matter?

It’s not a minor foreign policy issue.

Tehran—knowing they can’t match the U.S. and its allies in a one-on-one fight—is waging asymmetrical warfare - seeking to undermine, degrade, exasperate, and push the U.S. to overextend its military, diplomatic, financial, and political capital. (It was the Persians, remember, as early adopters of chess, who coined the term “shāh māt” (شاه مات), or “checkmate,” which translates into, “the king is helpless.”) That’s why Iran helped Russia arm itself with drone tech, shifting the tide of war in Ukraine. It’s why Tehran and North Korea cooperate on developing weapons of mass destruction, why the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei established elite cyber teams, and why its agents are funding and directing terror groups across the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and South East Asia. Tehran says it pretty clearly: “Death to America.”

So, cutting off the financing for this corrupt clerical regime is pretty much a top national security goal for the U.S. and Europe. And the U.S. can’t afford any more epic fails.

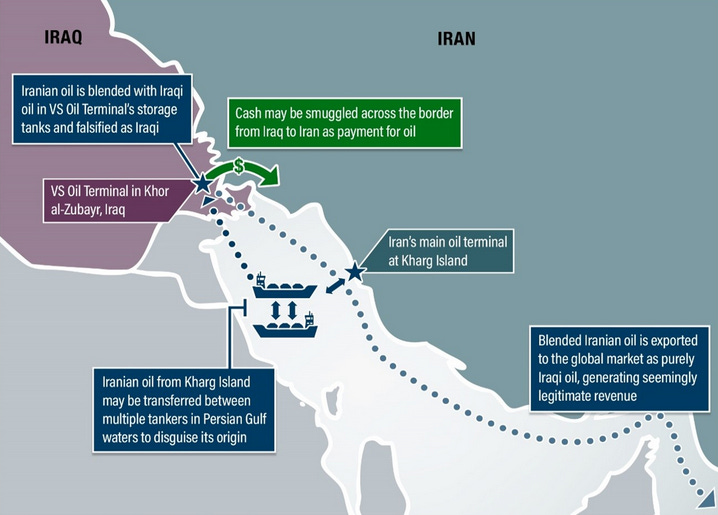

But Iran is running what it calls a Resistance Economy–its own shadow financial system that works with other “Axis of Evasion” countries to counter U.S. sanctions. Those clandestine operations allow it to export its oil, natural gas, petroleum products and other goods and services despite comprehensive sanctions barring financing, trade, insuring or transport of them.

To stymie those efforts, Treasury keeps rolling out sanctions against Iran’s prime revenue generation, like this network it sanctioned in July, even if it was three years after I exposed that particular smuggling operation.

But Tehran thumbs its nose at Washington in response, touting new export records. “This performance demonstrates the resistance and flexibility of Iran’s oil industry under sanctions,” the government-linked Mehr News Agency boasted.

This is not an isolated case: China, North Korea, Venezuela and Russia are learning to master the dark arts of sanctions evasion. Why hasn’t one of the biggest sanction packages in modern history worked on forcing Vladimir Putin to pull out of Ukraine?

New York Times reporter Aaron Krolic last week provided some insight into the missing policy ingredient, when he pointed out that few major banks–either domestic or international–have been penalized with sanctions or fined for sanction violations for the Russia program.

So, what is the missing policy ingredient?

Credibility.

Here’s what I mean: Sanctions policy is a lot like monetary policy in that a central bank’s power can shift the tectonic plates of the economic landscape by virtue of its potential power. A central bank, if it has credibility, can control the flow of money through economies with a few words and no actual action. Without credibility—the belief that the U.S. Federal Reserve will (or can) leverage its control over the dollar—markets will ignore any policy signals the Fed tries to send.

Mario Draghi, for example, was able to avert a collapse in the euro project with three little words—“whatever it takes”—because markets believed his vow was a credible one. (Note to President Trump: tampering with the Fed–including threats–undermines the Fed’s credibility, and you really don’t want to see what happens to the economy if it loses control of the dollar like the Bank of England did the pound in 1992.)

But US policymakers have lost critical credibility when it comes to enforcing sanctions, among other money-laundering threat-finance risks.

Companies operate on a risk basis, for profit. To change corporate behavior, the cost of falling foul of the law has to be worth more than income gained from questionable sources. And because corporations are run by people–(at least most haven’t been taken over by AI yet)–the people who are responsible for hiring, managing, and cultivating corporate culture and compliance systems have to be held to account for criminal activity under their watch.

If the financial costs/risk to the corporate bottom line and the criminal liability risks are insufficient, then companies and the individuals who run them will collectively flout the law.

Authorities need to raise the regulatory risk premium—domestically and internationally—to regain their credibility.

It’s not that there haven’t been large fines such as last year’s $1.3 billion TD Bank penalty. The 2023 $4.3 billion Binance settlement is credited as having helped many crypto platforms as a wakeup call to embed real anti-money-laundering protocols.

But there clearly haven’t been enough of them and/or they haven’t been large enough to force structural changes through the whole system.

Mirko Nazzari and Peter Reuter, writing in the University of Chicago’s Crime and Justice journal, came to a sobering conclusion in their 86-page study published earlier this year, How Well Does the Money Laundering Control System Work? (Sanctions-evasion requires money-laundering by definition, as it requires intentionally obfuscating the true nature of transactions.)

“There is no evidence that money laundering is declining or becoming more difficult or expensive. The system’s failure has many sources. Nations which pushed for its creation and development (particularly the United States) have been unwilling to implement critical elements. Major banks have repeatedly failed to meet their obligations, suggesting either insufficient commitment or a lack of the necessary skills and systems to comply effectively, despite substantial fines. Regulatory oversight had been inadequate. There is, however, evidence that the system aids enforcement of laws against criminal enterprises. Despite the consensus that the system works poorly, there is almost no discussion of substantial reforms.”

A study published last year by the U.S. Government Accountability Office into the effectiveness of anti-money-laundering laws found that there’s not even sufficient evidence available to determine whether those threat-finance rules are working. Notably, it cited the rollout of the Corporate Transparency Act as a top Treasury Department priority to address the systemic use of fronts and shell companies to launder dirty money as one of the key ways the federal government could counter money laundering and terrorist financing. That’s the one Trump’s Treasury, apparently at Elon Musk’s behest, gutted in March.

Other symptoms of credibility failure?

Why else would Goldman Sachs invest $865 million in Venezuelan bonds in 2017 even when the U.S. government had repeatedly decried the Chavista government as a narco-trafficking and systemically corrupt regime, and there was a substantial volume of evidence that the government used bonds as a laundering mechanism for corruption? (Or as Morgan Stanley put it in 2010, it had “identified Venezuelan bond transactions as presenting regulatory, AML, and reputational risk to the Firm.”)

Or take Interactive Brokers, the largest online retail brokerage in the U.S. The company was late last year fined a total of $38 million by the Securities Exchange Commission, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and this year hit with an $11.8 million settlement for anti-money-laundering violations in July by Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. That’s a lot of money to some folks, but it amounts to a regulatory hand slap when placed into the context that figure represents only 1.3% of the company’s 2024 pretax profit of $3.7 billion, and in light of its anti-money-laundering violations. OFAC said that between 2016 to 2021, IB operated hundreds of accounts in barred jurisdictions, including Iran, Syria and Russia-occupied Crimea, handling nearly 12,000 transactions for those customers; provided transfer services to sanctioned Russian banks; dealt in securities banned because of their links to the Chinese Military-Industrial complex. (And there are more yet-to-be-revealed inside revelations about how Interactive Brokers’ treated money-laundering concerns forthcoming from Blood Money Media.)

So, how can credibility be restored vis-a-vis Iran oil exports? The Trump administration should know.

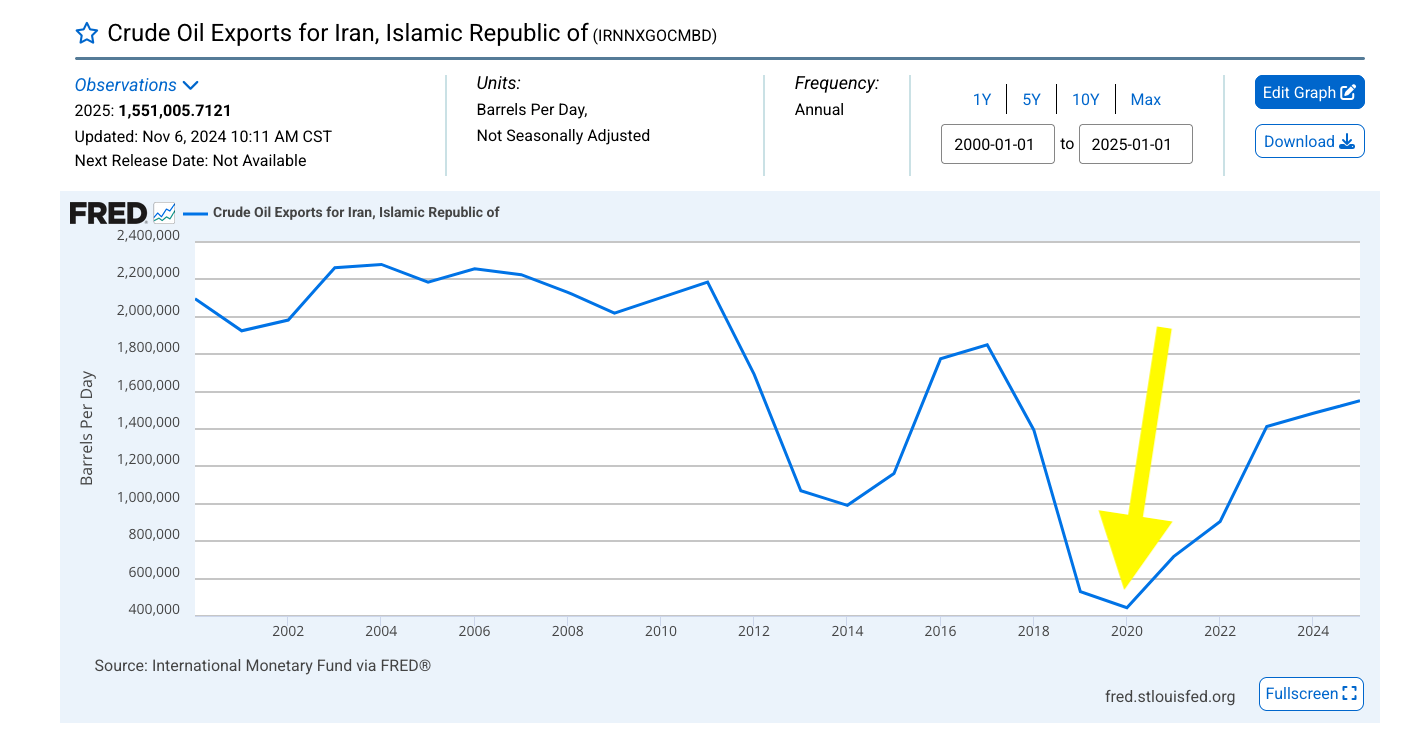

Take a look at this graph published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

One of the key reasons why there’s a precipitous decline in exports to a low in 2020 is because the State Department at the time conducted a specific campaign to warn nations commonly flagging ships transporting Iranian oil that they risked severe diplomatic and economic repercussions if they continued to provide suspected tankers safe haven. Ships without a flag not only find it incredibly difficult to find insurance for the voyages, but they also open the door to being boarded and seized by the U.S. and other jurisdictions.

One does not have to look far to identify common culprits because the U.S. Treasury includes in their sanctions against vessels their flagging nations. But some groups, like United Against a Nuclear Iran, have strategically prioritized tracking Iranian oil-smuggling operations through transponder and satellite data and notifying the flagging nations.

“In conveying our findings to the world’s flag registries, a majority have taken appropriate measures and de-flagged these vessels,” say UANI’s Claire Jungman and Daniel Roth in a post about what they’ve dubbed the “Ghost Armada.” “Others are less responsive, taking months to ‘investigate’ while allowing the vessels to engage in further illicit activity under their flag’s registration.”

For example, the Panama Maritime Authority was still flagging 116 of the 542 vessels in the Ghost Armada, according to Jungeman and Roth’s last calculation in mid August.

So, sanctions aren’t failing because they don’t work. They’re failing because of an erosion of credibility. If tankers can jump flags with no real consequence, if the private sector can treat money-laundering fines like an acceptable cost of doing business, if executives aren’t criminally prosecuted, if shell companies can keep hiding in plain sight, the U.S. is wasting valuable money, time, resources, political capital and lives–including those who regularly put themselves at risk because of the threats these powers pose—while Tehran and their partners stoke global chaos. The remedy isn’t more press releases (and taking credit for work conducted by folks whose work extends across administrations)—it’s a return to the kind of credible, coordinated enforcement that makes companies, banks, and flag registries believe that non-compliance is existentially risky.

Until Washington is willing to make that leap, Iran’s “resistance economy” will keep playing chess while America plays checkers.